Song Form in Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It” (1928)

An analysis of the melody in Cole Porter's first big hit, By Timothy Melbinger (01/05/2024)

This paper will analyze the vocal melody of Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It (Let’s Fall in Love)” in an attempt to discover how it holds the song together. As I cannot identify melodic notes without reference to harmony, I will discuss that parameter when necessary. I will be using a kind of overlaid Schenkerian Analysis in order to call attention to the structural notes and then overt Schenkerian reductions when approaching longer periods, for I believe Porter must have had some familiarity with the kind of foreground and background voice-leading that Schenker’s approach is so useful in describing. American Cole Porter (1891 – 1864) wrote the song that would help launch his fame for the musical Paris, his first stage success (on Broadway, in 1928). It is one of several songs in the production written specifically for the star singer, Irene Bordoni. “Let’s Do It” is most loved for its lyrics and there are a lot of them! It is a “list song,” with several refrains offering a wide variety of the way “it” is done around the world. The clever part is that every verse reminds us that “it” is not the sex that he implies, but actually stands for falling in love, which means the listener has to revise his naughty thoughts along the way. Bordoni must have sold the witty lyrics effectively; I cannot think of a Broadway-type singer who could resist running around the stage in doing so.

It is not clear what instruments would have played the original version; all I can go by is the piano/vocal arrangement from The Cole Porter Song Collection (Alfred). This version bears a 1928 copyright, so it is the sheet music you could have purchased at the time. It is sufficient for this analysis, although the pianist (per the sheet music convention) does double duty playing the harmony and harmonic support, which almost certainly would not have been the case during the show for which the song was written.

I’ll be discussing the form, and specifically the two manifestations of the American Popular Song Form (also called Ballad Form), such as it was in the late 1920s and the Tin Pan Alley period. As the form was ubiquitous in not only Porter’s music but many songwriters at the time, it is good to know how it works, how these two versions of the form differ, and to what effect.

Overall, there are two large parts to the song – the introductory verse and the refrains (sometimes called the “choruses.”) These parts are by no means equal. The function of the verse, besides introducing some of the melodic and harmonic materials for the whole song, is to form a big upbeat which sets the stage for the downbeat of the refrain. After this, the verse does not return, so the song is lopsided in favor of the five (!) refrains and all of their silly double-entendre lyrics.

Song form is expressed in the letters AABA. That means a repeated first phrase leads to a contrasting third phrase before the section that concludes with a return to something closely related to the first phrases. Each letter and phrase, moreover, is the same length. This description is a broad outline, for we almost always hear significant variations in the second and third versions of the A phrases, such that we refer to them as A, A’ (A prime), and A” (A double prime). I should point out that this form is certainly NOT exclusive to American Songs, for it has been part of concert music and folk songs for hundreds of years in many places.

PIANO INTRODUCTION AND INTRODUCTORY VERSE

The introduction consists of one phrase, while the verse is comprised four phrases in an AABA’ form. The primary purpose of the piano introduction is to establish B-flat major and reach the dominant as an upbeat for the coming vocal phrases. Porter’s melody is a type of arch; it ascends from F4 to B-flat4, jumps to G5, and descends to C5. His harmony supports the two halves of the arch with tonic and dominant – resulting in an open ending. Three details to enjoy here, a) the last thing we hear in the left hand of the piano is G-Gflat-F – it becomes the first idea in the refrain (with the words “Let’s Do It”), and b) we hear the dotted-eighth/sixteenth rhythm first and four times total – this is an introduction to one of the most important rhythmic ideas in both the verse and the refrain, and, c) The high note is G5 and that is not trivial, for high Gs play an important part in the verse’s first two phrases.

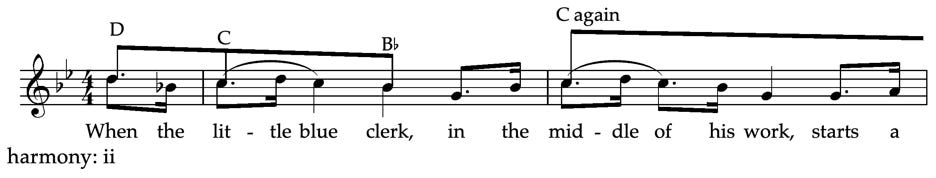

Verse vocal phrases one and two (both A) are identical (except for the words), which means that the second phrase further emphasizes what phrase one does. Each is four measures long; this establishes the importance of this length of time – the phrase periodicity. Porter establishes a G-F emphasis – the dominant note and its upper neighbor – with five of the first six notes before filling in the lower part of the scale and then flying up to D5 for a weak and somewhat enigmatic ending – he wants us to hear the final notes as much higher than the melodic focus of the first half of the phrases. Note that the melody ends on D5, yet the piano continues the ascent by jumping to G5. Not only was this the high note to which he lept in the piano introduction, but it is another kind of G, which sounds right as the lower G had not been displaced by another pitch in the middle of the phrase; they both hang there and beckon to the next phrase. His harmony is a simple closed tonic-dominant-dominant alternation. Details to enjoy here include the internal rhymes: “bluebird” and “word,” and “sing” with “spring.” These last two rhyme with the end of the second phrase’s “ring” and “ding.”

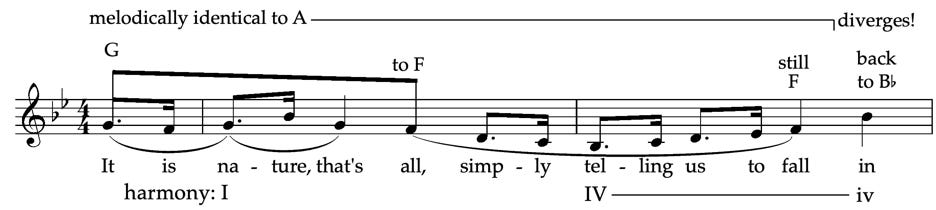

Verse vocal phrase three (B) is a welcome contrast. It is also four measures long, but unlike the first two phrases, the voice proceeds all of the way to the downbeat of the fourth measure rather than bowing out for piano echoes. Porter’s melody moves from D5 – a continuous move with the end of the A phrases – through C5 and then Bflat5 (twice) before jumping back to the G4/F4 axis for a weak ending. The harmony moves to V, an open ending that contrasts the tonic endings from the first two phrases and sets up a necessary resolution for the whole section in the fourth phrase. Note the tension between the ending on F4 with dominant harmony when this F was part of tonic harmony in phrases one and two. It means that, while we haven’t gotten away from the initial harmonic emphasis, at least the harmony is beckoning for resolution.

Verse vocal phrase four (A’) begins as a repeat of phrases one and two; it diverges halfway through with a sudden resolution on Bflat4 – a strong cadence. This is odd, as we hear no stepwise move to the Bflat. Yet this is what the beginning of the phrase three (B) was doing, as we heard D5 – C5 – B-flat4 motion there (before he suddenly left it for the G/F axis). His harmony moves from I to IV (and minor iv) before a weak cadence on I. It seems odd that the section has a weak cadence, but it is okay as this is not the chorus and we do not need a rock-solid conclusion here. Actually, the section is not truly over with the arrival of tonic harmony in the third measure (of four measures). Quickly, two more things happen, a) we hear a return of the G5 notes as an interlude, and, b) he harmonizes four of the seven Gs with the dominant harmony (as V9!), which makes this the real harmonic goal of the section. Like the piano introduction, we hear dominant harmony at the end as an upbeat for the tonic that will begin the next section. The plagal cadence in the previous measure was no more than a comma, for this dominant harmony stands out and heralds the beginning of the refrain.

Overall, the introduction/verse is charming. Regarding pacing, note that the fits and starts from the first two phrases give way to a more continuous phrase (B) that hinged upon the D5 from the “ding, ding” pause. For the end, he reminds us of the first phrase but changes it just in time to avoid falling into the same path while finding closure, yet also just early enough to reset the table for a big upbeat to the coming downbeat of the refrain. I mentioned an overall unity that the individual phrases lacked (the seemingly strange high D moves to C in the B-flat (B phrase) and ends with B-flat as part a larger descending line to the sudden B-flat tonic (A’ phrase)), yet what are we to make of all of the G-F axis? Well, he certainly flagged it for consciousness and it is currently hanging there. Sure enough, he’s going to do a lot with it in the refrain.

THE REFRAIN

The focus of the song are is the four vocal phrases – all eight measures long and in an A A’ B A” form – that constitute the refrain. It contains the title words and all the variations of things that “do it.” Like the verse, we hear a combination of repetition, with an A, A’ and even A” phrases, and contrast, with a far-reaching B phrase. The final phrase, as we would expect, delivers the climax, which includes the high notes and, by far, the most conclusive melodic and harmonic ideas in the song. I’m going to discuss only the first time through the refrain, yet it is essential to point out that it has FIVE iterations, which means it dwarfs the introduction/verse in importance. The most obvious detail to keep track of is Porter’s elaboration upon the G/F axis – with a passing G-flat that falls on strong beats and it particularly dissonant with the harmony. As we hear it on the verb “do,” it is supposed to sound nasty – it helps us have the impression that “do it” means sex in a somewhat unsavory way! He will quickly pull the rug out from under us – doing it means falling in love – this is, of course, the most charming part of the song.

The refrain phrase one (A) melody begins (again) with the G-F axis, and with the aforementioned chromatic G-flat. He repeats this three-note descent before climbing up to C, returning to G-F, then suddenly dropping to low D for a weak ending (this may remind of the sudden leap to D in the verse phrase one melody). The harmonic support is a closed progression: I – ii – V – I (we haven’t left B-flat major whatsoever). Rhythmically, note the three consecutive iterations of the dotted eighth rhythm that put a bounce into the melody after the rather deliberate beginning.

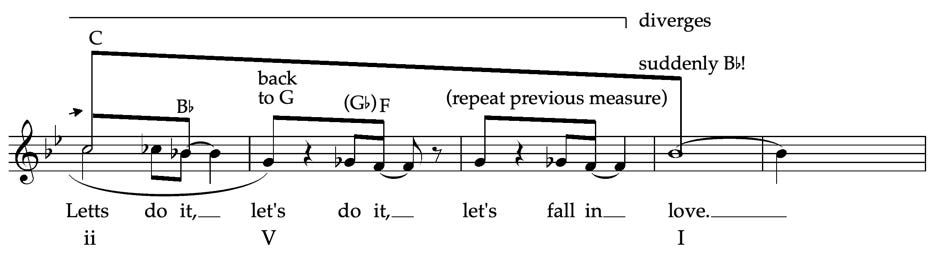

His melody and harmony in the refrain phrase two (A’) are nearly the same as in phrase one, with one exception, as he jumps to B-flat4 at the end. This is a stronger ending, yet – like the end of the verse – it doesn’t directly come from a step (A4 or C5) right before it, so we are not tempted to stand up and clap for the ending. Like the end of the verse, the jump to B-flat4 does connect to earlier motion from the local high note, C5, so it is not a complete non sequitur. Note the delicious homophone: let’s and Letts – something you would only appreciate from the context of Lithuanian and Letts (although he means Latvians!).

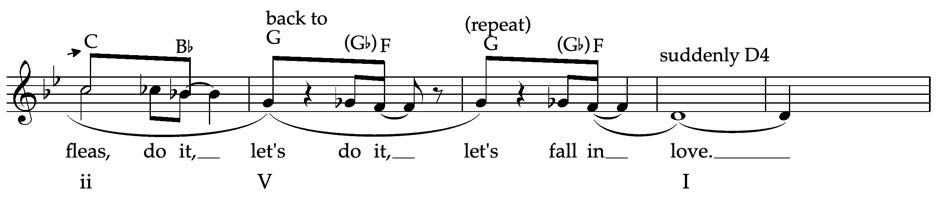

The severe contrast in the refrain phrase three (B) is necessitated by the near repetition of the A phrases. It is melodically strange, as he moves down by descending half steps, structurally, in each measure. Along the way, the harmonies are relatively chromatic, with no hint of the tonic harmony. He begins with the same B-flat from the end of phrase two, with what sounds like a transposition of the melody up a third. The third and fourth measures are a chromatic link – note the prominent A-flat4 pushes the melody down to two lower version of the “…do it” motive, one beginning on G and another on F G-flat and then F for an open ending with dominant harmony. Note that the last three notes in this descent are G – G-flat – F, which is, of course higher notes, such as the B section from the verse, but he decided to elaborate his new theme instead. It is clever; perhaps he envisioned this ending first and found a way to have the phrase anticipate it.

The refrain phrase four (A”) begins as an exact repetition of phrase one – note that this happened with the last phrase of the verse. Yet after two measures, he modifies his ascent to climb past C to E-flat! It is deliberate, as well, with noticeable pauses on D-flat5 and D-natural5. The D5 (on a final “let’s do it”) is the arrival and the E-flat5 is the icing on the cake – it’s an ecstatic neighbor to D. Recall that this high D was the previous high note, which makes the E-flat5 diversion even more special. From this D hinge is a direct descent to B-flat5 as part of the strongest cadence in the song. This is the kind of stepwise descent that was notably lacking from the two phrases that ended on B-flat5 earlier in the song.

From the following graph, and as in the verse/introduction, note just how much G/F music we hear (albeit with the fresh G-flat now!). Also like the verse/introduction, the melody climbs higher, occasionally, to a C/B-flat axis. Note how, in the first three phrases, there are phrase endings on D and F – though part of the tonic triad, they are both inconclusive and serve as brief pauses. before the end. But, unlike the verse introduction: the final phrase here is conclusive harmonically and especially melodically, as a result of the explicit move down to B-flat4 from above.

CONCLUSIONS

While the lyrics are saucy and genuinely witty, Porter sets them to music with a solid and effective melodic design. The verse introduction and the refrain(s) present two kinds of AABA song form. In both cases, the final phrase is varied enough to make an ending, yet the verse introduction is weaker. This is as it should be, as we want to hear that the song is continuous in anticipation of the refrain. The final measures of the refrain are the climax of the song – again, as they should be – so that we know that the refrain is ending. His variation of the melody at the climax is FAR more deliberate, direct, and goal-oriented than any of the previous phrases.

While B-flat is the tonic and he does end there, I would identify the G/F axis as the focal point of the song – from which other things emerge, such as the varied ends of phrases. The addition of the passing-yet-accented-G-flat before F for the title words clinches the argument for G/F primacy. The F, however, is never displaced by an E-flat in scalar descent to the tonic; it remains as a fixed star from which the D, C, and B-flat are satellites. This isn’t new; Chopin occasionally did this and perhaps those songs rattled around Porter’s memory from his piano-lesson days.